Stone Reading

Stone Reading

video, 6’55”

2014

Video essay about life’s origins, organic and inorganic life, the soul and the unconscious.

Part 1

Part 2

The Longue Durée meets Deep Time: Marina Roy’s Entangled Worlds

By Randy Lee Cutler

In the early 1800s Alexander von Humboldt the Prussiangeographer, naturalist, explorer, and nascent scientist described the natural world and man’s place within it as a complex web of life. Interpreting the natural world as a unified whole that is animated by interactive forces, Humboldt became the first scientist to address the devastation of the environment through exploration and colonization.[1] More than two hundred years later we find ourselves inhabiting a world ravaged by human-induced climate change. Today we call this the anthropogenic impact on the environmentor the Anthropocene[2], the current geological age where human activity is the dominant influence on climate and ecology. With the seemingly endless proliferation of digital media from cell phones and computers to lens based practices, the mining of metals has contributed to this phenomenon. Life across the boundaries of geology and history, art and culture present a world order that is imbricated, an entangled complex web of life.

For more than two hundred years we have endured the onslaught of rapacious industry and its impact on all living systems from biomass and energy to decay and extinctions. This extended event or longue durée frames the larger temporal framework of our own time. The longue durée (orthe long duration), an approach to history employed in the 1950s and 60s by the French Annales School of historical writing,looks at shifting patterns over longer time frames, like 100 or 200 years. The Oxford dictionary offers this definition of the term:

“A perspective on history that extends deep into the past, focusing on the long-standing and imperceptibly slowly changing relationships between people and the world which constitute the most fundamental (and hence the least questioned or analysed) aspects of social life, and incorporating findings from disciplines such as climatology, demography, and physical geography…”[3]

By looking at long term patterns and shifts in society rather than significant events or important individuals, deeper background rhythms to historical change surface where invisible currents frame not only the existence of the human species but that of our living planet Earth. In this way the longue durée of human activities folds into the larger frame of deep geological time. Deep Time invokes a geological, multi-millennial time frame that is both historical and material. Within these distinct yet overlapping time structures, we find ourselves inhabiting multiple time scales where short and long term human time is experienced through and within the deep time of geological epochs.While this complex web of life is understood primarily through the sciences, its potential for expressive and poetic provocation is simultaneously navigated through the social sciences, aesthetics and the imagination.

I speculate here on the braiding of the longue durée and deep time as a means to consider time and materiality through variegated time-scales that are interconnected. According to Donna Harawy in her book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene she considers tentacular thinking or tentacularity which “is about life lived along lines –not at points, not in spheres.”[4]These lines form trajectories with a broad reach and tangled implications which ensure that we stay with the trouble, refusing both the nostalgic angling towards an imagined past that never was and the apocalyptic orientation towards a future that may not be, or, at very least, isn’t yet. How do we draw these temporal lines of flight and fight? How do we make sense of the often sublime interactions between human and natural histories never mind human and natural time scales? These thoughts are tentacular questions of learning to live and of learning to die in our current historical moment. Looking through the longue durée and deep time is a kind of tentacular thinking, reaching its tentacles across space and time, matter and memory. How do we endure this sensorial phenomenon of living in an increasingly toxic world?

Of course these ideas are not new. Indigenous ways of knowing and being with the land is attentive to the longue durée and deep time with its inherent respect for the natural world. TheSeventh Generation Principleis based on Iroquois philosophy that the decisions we make today should result in a sustainable world seven generations into the future. “The first recorded concepts of the Seventh Generation Principle date back to the writing of The Great Law of Iroquois Confederacy, although the actual date is undetermined, the range of conjectures place its writing anywhere from 1142 to 1500 AD.”[5]This principle, like approaches of the longue durée and deep time, offers us the opportunity to reconcile with the planet that feeds and sustains us. Importantly, the Anthropocene is not universally applicable. Many indigenous scholars dismiss this concept mostly because the human impact does not reflect the practices of indigenous peoples. For instance Zoe Todd seeks “to decolonize and Indigenize the non-indigenous intellectual contexts that currently shape public intellectual discourse, including that of the Anthropocene.” In particular her research highlights how “the current framing of the Anthropocene blunts the distinctions between people, nations and collectives who drive the fossil-fuel economy and those who do not”. She adds that it is important to ask, “…whichhumans or human systems are driving the environmental change the Anthropocene is meant to describe”.[1] These are necessary questions, which augment and intensify how we make sense of these troubling times. And yet the term Anthropocene, fraught with cynicism and imprecision points to a global planetary signature. ”We are all involuntary prisoners.”[6]

a b

A geological-biological-historical orientation permeates the work of Vancouver based artist Marina Roy whose cross-disciplinary practice has been exploring the intersection between materials, history, language, and biopolitics from a post-humanist perspective. Her experimental aesthetic embraces the potential of a restorative vs. extractive economy that counters the dictates of humanistic hubris and its entrapment within binary power dynamics where art acts as a bridge between culture and nature, ethics and drive. Roy’s recent practice has focused on environmental degradation and animal extinction as an historical reality. It speaks to the negative transformations in nature, largely due to human industry. A selection of her work such Stone Reading(14 minute video) 2017, Mal de Mer, (45 minute video) 2016, Thy Kingdom to Command (25 meter mural and tree stump fountain)2016 andApartment(56 minute animation) 2018, demonstrate a sustained engagement in material experimentation and the effects of human activities on biological life.

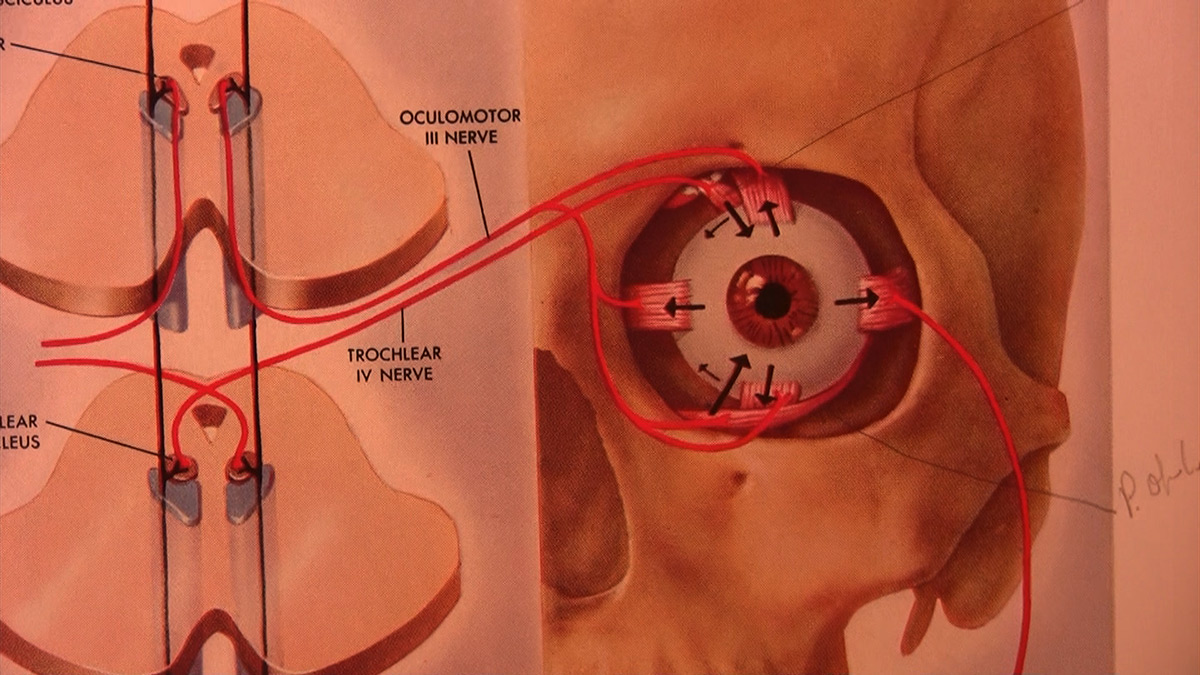

Stone Readingexplores these themes in the form of a video easy. The work begins with a slow pan of small objects on a windowsill accompanied by a low-key voiceover that speaks to deep time. “It has been decided that humans are a geological force to be reckoned with. The Earth is dominated by human’s heavy presence on the planet, an accumulation of their superstructure’s ruins and waste. So many indelible marks left behind by the species.” As the narration unfolds we watch a pair of hands holding and turning over different mineral specimens and asked to consider the anthropogenic effects of human activity. The stones are a visualization of the deep time of the Earth signaling the literal depth of the temporal past and technological present. The collaged video is comprised of things that the artist shot from museum artifacts and bubbling water in a hot tub to medical illustrations of the human body and objects laying around her home. As she tells it these sequences have been catalogued in a haphazard fashion to be reconfigured later in relation to her written text which addresses geological time, the spectrality of the photographic medium, the search for the soul, as well as psychoanalysis and the unconscious. The effect is a visual improvisation on the speculative materiality of history. Here Roy brings an interest in technology to reflections on the imagination. “The mimetic machines such as cameras bring to life the spectrality of our fleeting world helping us to discover an optical unconsciousness made possible by our interfacing with technology, opening up new possibilities for exploring reality and envisioning a new reality.” The camera work echoes this entangled orientation with its mixing of fact, fiction, mimeticism, storytelling, and art. The geological time sense highlighted here further collapses scientific, philosophical and informal knowledge practices and in the process points to new architectures of time and matter. Thisarchaeological dig across geographies and histories works in a tentacled, non-hierarchical and somatic way. Roy condenses and displaces looking while elucidating and transforming our felt sense of time. The diverse elements and mixed timescales put the emphasis on a diversity of languages and disciplinary interests that do not reproduce the illusions of linear coherence; Roy’s attentions are neither idealist nor concerned with civilizational progress. This punctuated way of seeing is a kind of emergent way of knowing that echoes the temporal imperatives of deep time.

Underground phenomena and invisible to the eye are made manifest through Roy’s hybrid gaze. In her large 25 meter mural and tree stump fountain Thy Kingdom to Command2016 she works with the signature of deep time to explore the ongoing effects of processed materials. Here latex paint and bitumen, the sticky, black, semi-solid form of petroleum become the symbolic carrier for investigating short and long time scales. Taking the form of strata, the material is used to create a multitudinous array of life forms from the microscopic to life size. Here deep time and the longue durée fuse into a spectacle of life forms across eons that are simultaneously natural and artificial. The physical scale of the work speaks to the sublime impact of our addiction to petroleum and petroleum products. The work was commission by the Vancouver Art Gallery for Offsite, their outdoor exhibition space that is experienced by pedestrians but also by drivers on their daily commute across the city. The artist’s intention was to make the connection between car culture, fossil fuels and environmental crisis in a visually striking encounter. In many ways the natural and manufactured are understood as part of the larger processes and rhythms of material evolution and material degradation.

Roy’s practice engages with a speculative geo-biology, a morass of geohistories and biopolitics that call attention to the invisible realities of the extraction of coal, oil, and gas, and theiratmospheric consequences; the combustion of carbon-based fuels and emissions;coral reef loss; ocean acidification; soil degradation and the increasing rate of animal extinction. The transformation of materials brings nature into exquisitely haunting images where human endeavour via resource extraction is framed within the longue durée of history.Drawing from the connections between biopolitics and her environmental readings, Roy’s artwork often assumes the perspective of the more than human world whether stones, crude oil, microscopic viruses or creatures from the wider animal kingdom. In her beautiful cell and collage animation Apartment(56 minutes) 2008 a creaturely presence frames a world outside human clock time suggesting a post-humanist perspective that imagines temporality beyond the all too human. In this work various animals (horse, panda, bat, bee, rhinosaurus, squid, pig, whale, cow and microscopic virus) are juxtaposed with skeletal forms and human figures from history. Unfolding through a slow, dreamy pace where time is not specifically human, the video moves through a dilapidated apartment block. Each of the 100 rooms with their late 18thcentury watercolour interiors is revealed as a backdrop where animals, human and otherwise, perform strange actions and gestures. As the work unfurls we learn that a mysterious virus has colonized the building and infiltrated the conventional order of things. Graham Meisner’s sound composition furthers the eerie sense of an unfamiliar place set in an unidentified time. The fact that the animals have taken over the building suggests perhaps their resilience within and beyond this human made world.

Mal de Mer 2016, recently shown in the Nanaimo Art Gallery’s exhibition Landfall and Departures: Prologue is a time based work that considers the substrate of the sea from a creaturely point of view. In this iteration, the piece begins on the seabed and looks up toward the water’s surface as if through the perspective of a crustacean crawling on the ocean floor. Kafka’s transformed character Gregor Samsa into a scuttling insect from The Metamorphosiswas the initial inspiration for the piece. By dropping a GoPro into the water in the Salish Sea, Roy works with metaphors of fishing and hunting with the camera. Exploring and undermining its own machinic agency, the camera is also the bait dangling from a line in the water. The accompanying audio by Meisner offers a vibrating, often jarring soundtrack that furthers the alien point of view. As the video unfolds we are immersed in the sounds of water and movement. Fish swim by and golden algae undulates across the creature’s field of vision. All variety of sea life inhabits this beautiful yet alienating world full of marine plants and fungi. At times the pillars from a wharf come into view encrusted with white lichen, orange and brown barnacles and purple starfish. The kaleidoscopic effect is mesmerizing taking us out of time into a temporal experience that is perhaps more animal than human. Through the camera’s eye we are subject to an amateur almost alien aesthetic that questions the ontology of looking. Roy’s deskilled approach draws from conceptual art and brings a more than human sensibility to the fetishized glossy image. Given the artist’s longstanding investigation of otherworldly, post humanist worlds, Mal de Mer reads as an offering, a window into the two thirds of our planet that is, like us, predominantly water.Informed by philosopher Elizabeth Grosz’s book Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth, Roy’s planetary investigations manifest the expressive potential of the forces of the planet and of art itself.

“The forces of the earth (cosmological forces that we can understand as chaos, material and organic indeterminacy) with the forces of living bodies, by no means exclusively human, which exert their energy or force through the production of the new and create, through their efforts, networks, fields, territories that temporarily and provisionally slow down chaos enough to extract from it something not so much useful as intensifying, a performance, a refrain, an organization of color or movement that eventually, transformed, enables and induces art.”[7]

Slowed down measured energies with their more than human articulation are echoed in the long duration of Mal de Mer,suspending the viewer into a netherworld that offers insight into a different temporality, a different time sense. This is inflected by our increasing awareness that our actions are pushing the world’s oceans closer to the brink of destruction. Submerged in this aquatic spaciousness we are left to wonder about the delicate balance of this liquid realm which is usually out of sight and therefore out of mind. Humans as a global geophysical force inform the movement and materiality of Mal de Mer with its real, symbolic and imaginary expressiveness. Even as the work celebrates an aquatic world tingling with life, we are reminded of its precariousness within the longue durée of time. The Earth is alive, rhythmic, undulating and mutating in response to human activity.

Much of Roy recent work reveals how an artist identifies and ruminates on large scale temporal and unseen processes and speculates on their affects through sound and image. This is afforded by an approach that develops narratives for this historic moment beyond disciplinary focus; informed by scientific data, social science analysis and intuition Roy’s practice seeks to share with the viewer the cosmological forces that connects humans to stones and animals to temporal rhythms. Orienting her gaze beyond shallow time, Roy’s experiments engage with history at multiple time scalesexposing the inadequacy of the short view. Her broad interests in philosophy, history, biology and the natural world intersect spatiotemporal fields wherein a larger view is produced, one that connects us to the entangled world that we inhabit. Perhaps we need learn to collaborate not just across species but also across time. This kind of tentacular thinking reaches its tentacles across space and time proffering a human reconciliation with the local, the imagination and the planet itself. It has been more than two hundred years since von Humboldt first described the natural world as a unified whole animated by interactive forces. More recently we have amassed abounding sources of big data that describe a new ecosystem, which draws on and incorporates findings from climatology, geography and demography to history and geology.

In this experimental artistic approach one must not be afraid to develop new processes of working, taking up materials and technologies that connect us to deep time. It calls for a redefinition of boundaries between disciplinary fields that entangle conceptual and scientific languages where temporalities of terrestrial mutation reveal different epistemologies, alternative ways of knowing. Perhaps these knowledge limits are the way forward toward a restorative perspective, one that takes into account the longue durée. Art, central to thinking with and feeling through the Anthropocene, occurs at a number of strata and across various time scales.Marina Roy offers a range of discursive, visual, and sensual strategies that experiment, record, modify and recreate ways of imagining life.Through her generous practice we are asked toendure our encounter with planetary crisis and catastrophic loss on many levels by acknowledging that we reside in, affect and are affected by multiple time scales. How do we inhabit time, learning to live and of learning to die in our current historical moment?

[1]See “Indigenizing the Anthropocene” in Art and the Anthropocene, Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and EpistemologiesPaperback, 2015

[1] Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature, The Adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt The Lost Hero of Science, John Murray Publishers, 2015, p. 32.

[2] The term first popularized by the Dutch chemist Paul J. Crutzen in a 2002 paper he published in Natureencompasses various anthropogenic effects, including, but not limited to: the rise of agricultureand attendant deforestation; the extraction of coal, oil, and gas, and their atmo-spheric consequences; the combustion of carbon-based fuels and emissions; coral reef loss; ocean acidification; soil degradation; a rate of life-form extinction occurring at thousands of times higher than throughout most of the last half-billion years. H Davis and E Turpin, “Art & Death: Lives Between the Fifth Assessment & the Sixth Extinction” in Art and the Anthropocene, Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, p.1–4

[3]https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/longue_duree

[4]http://www.e-flux.com/journal/75/67125/tentacular-thinking-anthropocene-capitalocene-chthulucene/

[5]https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/seventh-generation-principle

[6]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=baMWCx6kwoo

[7] Elizabeth Grosz, “Chaos. Cosmos, Territory, Architecture”, 2008, p. 3–4.